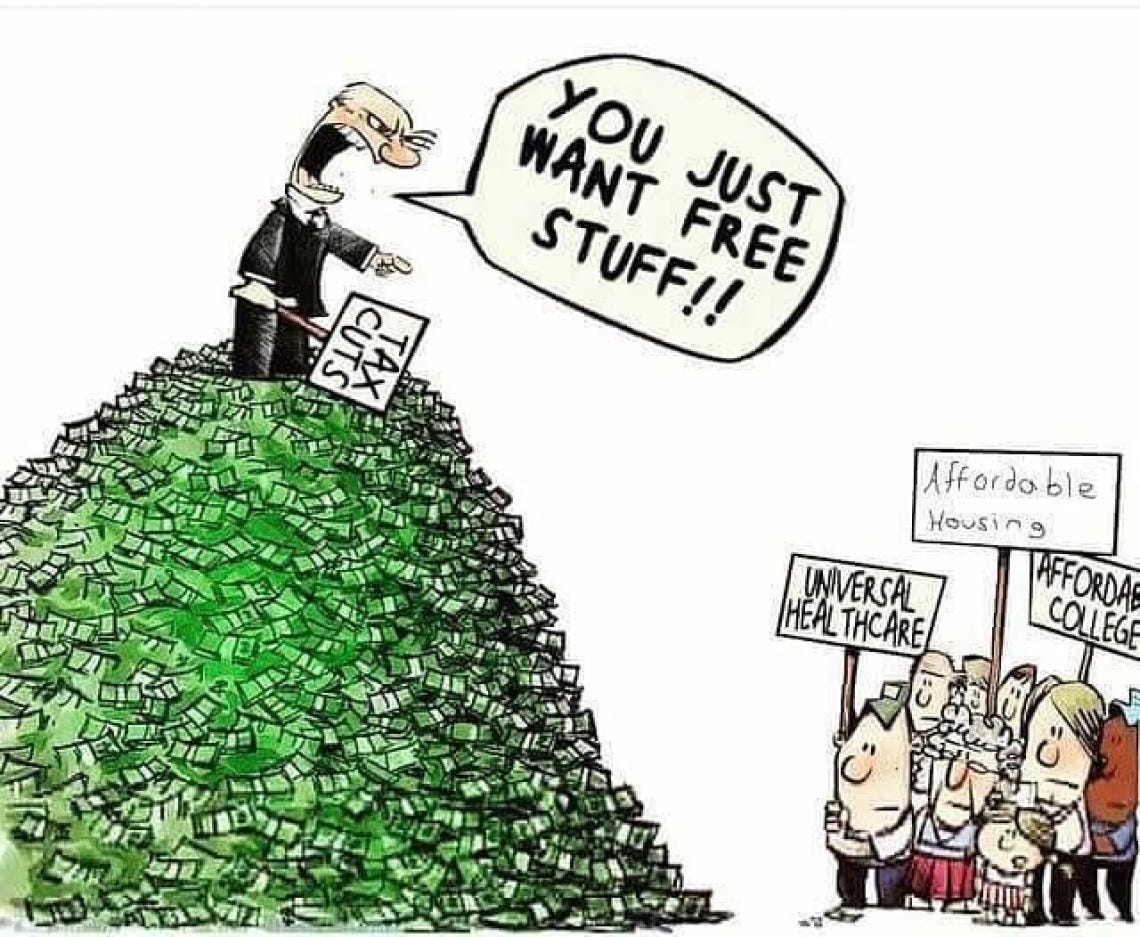

Almost a decade ago, Warren Buffett made a claim that would become famous. He said that he paid a lower tax rate than his secretary, thanks to the many loopholes and deductions that benefit the wealthy.

His claim sparked a debate about the fairness of the tax system. In the end, the expert consensus was that, whatever Buffett’s specific situation, most wealthy Americans did not actually pay a lower tax rate than the middle class. “Is it the norm?” fact-checking outfit PolitiFact asked. “No.”

Time for an update: It’s the norm now.

For the first time on record, the 400 wealthiest Americans last year paid a lower total tax rate — spanning federal, state and local taxes — than any other income group, according to newly released data.

The overall tax rate on the richest 400 households last year was only 23%, meaning that their combined tax payments equaled less than one quarter of their total income. That was down from 70% in 1950 and 47% in 1980.

For middle-class and poor families, the picture is different. Federal income taxes have also declined modestly, but these families haven’t benefited much, if at all, from the decline in the corporate tax or estate tax. And they now pay more in payroll taxes (which finance Medicare and Social Security) than in the past. Overall, their taxes have remained fairly flat.

The combined result is that over the last 75 years the U.S. tax system has become radically less progressive.

The data here come from the most important book on government policy that I’ve read in a long time — called “The Triumph of Injustice,” to be released next week. The authors are Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, both professors at the University of California, Berkeley, who have done pathbreaking work on taxes. Saez has won the award that goes to the top academic economist under age 40, and Zucman was recently profiled on the cover of BusinessWeek magazine as “the wealth detective.”

They have constructed a historical database that shows how much households at different points along the income spectrum have paid in taxes going back to 1913, when the federal income tax began. The story they tell is maddening — and yet ultimately energizing.

“Many people have the view that nothing can be done,” Zucman told me. “Our case is, ‘No, that’s wrong. Look at history.’ ” As they write in the book: “Societies can choose whatever level of tax progressivity they want.” When the United States has raised tax rates on the wealthy and made rigorous efforts to collect taxes, it has succeeded in doing so. And it can succeed again.

Saez and Zucman portray the history of U.S. taxes as a struggle between people who want to tax the rich and those who want to protect the fortunes of the rich. The story starts in the 17th century, when northern colonies created more progressive tax systems than Europe had. Massachusetts even enacted a wealth tax, which covered land, ships, jewelry livestock and more.

The southern colonies, by contrast, were hostile to taxation. Southern plantation owners worried that taxes could undermine slavery, as historian Robin Einhorn has explained, and made sure to keep tax rates low and tax collection ineffective. (The hostility to taxes ultimately hampered the Confederacy’s ability to raise money and fight the Civil War.)

By the middle of the 20th century, the high-tax advocates had prevailed. The United States had arguably the world’s most progressive tax code, with a top income-tax rate of 91% and a corporate tax rate above 50%.

But the second half of the 20th century was mostly a victory for the low-tax side. Companies found ways to take more deductions and dodge taxes. Politicians cut every tax that fell mostly on the wealthy: high-end income taxes, investment taxes, the estate tax and the corporate tax. The justification for doing so was usually that the economy as a whole would benefit.

The justification turned out to be wrong. The U.S. economy has not fared better when tax rates are lower. Lower taxes on the wealthy instead end up benefiting the wealthy, not society as a whole. The great decline in high-end taxation has happened over the same period that economic growth has been disappointing and middle-class income growth even worse.

That’s the maddening part of the story. The energizing part are the solutions that Saez and Zucman propose. They call for a set of policies that would raise the overall tax rate on the wealthiest Americans to about 60% (still not as high as in 1950). Doing so would bring in about $750 billion a year, or 4% of GDP, enough to pay for universal pre-K, an infrastructure program, medical research, clean energy and more. Those are the kinds of policies that really do lift economic growth.

One crucial part of the agenda is a minimum global corporate tax of at least 25%. A company would have to pay the tax on its U.S. operations even if it set up headquarters in Ireland or Bermuda. Saez and Zucman also favor a wealth tax; Elizabeth Warren’s version is based on their work. And they call for the creation of a Public Protection Bureau, to help the IRS crack down on tax dodging.

I already know what the critics will say about these arguments — that the rich will always figure out a way to avoid taxes. That’s simply not the case. True, they will always be able to avoid some taxes. But history shows that serious attempts to collect more taxes usually succeed.

Ask yourself this: If efforts to tax the superrich were really doomed to fail, why would so many of the superrich be fighting so hard to defeat those efforts?

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

No comments:

Post a Comment

After you leave a comment EAT!